What Fire Emblem, XCOM, and Tactics Ogre can teach us about real-world power structures.

By Dr. Lilah Faraday

GamingGraduate.com

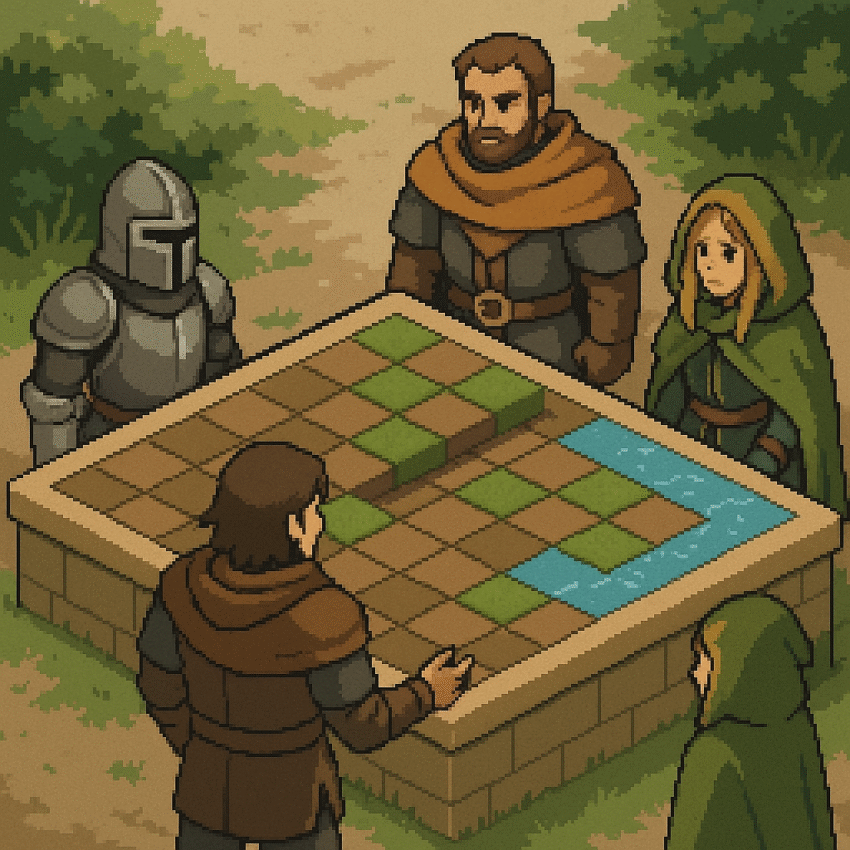

Faction design in tactical RPGs is rarely accidental. From color palettes to class availability, from governing ideology to battlefield deployment, how a faction presents itself and functions within a game’s ecosystem is often more than a matter of lore. It is an act of simulation—a reflective device that channels real-world political systems through combat mechanics, dialogue trees, and moral dilemma.

It’s tempting to reduce faction-based games to simple archetypes: the militarists, the mages, the merchants, the rebels. But such reductionism ignores the intentionality baked into these structures. Tactical RPGs—by virtue of their methodical pacing and systemic depth—provide fertile ground for political allegory. The battlefield becomes a stage for ideologies to clash not just narratively, but mechanically. Who gets to act? What tools do they use? How are their hierarchies enforced? What are they willing to sacrifice?

Let us dive—grid-by-grid—into the symbolic function of factions and the political grammar that underlies some of the genre’s most iconic strategy games.

I. Fire Emblem: Houses of Power and Pedagogy

When Fire Emblem: Three Houses released, it did something few tactical games dared: it put players in charge of ideological grooming. As a professor at the Officers Academy, you choose one of three houses—Black Eagles (Adrestia), Blue Lions (Faerghus), or Golden Deer (Leicester)—each representing a separate political entity in the continent of Fódlan.

At first glance, the choice feels like a matter of character preference. But upon deeper play, you discover that each house is a political education engine.

- Adrestian Empire (Black Eagles): An old monarchy teetering on totalitarian reform, flirting with fascism masked as meritocracy.

- Holy Kingdom of Faerghus (Blue Lions): A feudal structure obsessed with honor and vengeance, effectively a militarized theocracy.

- Leicester Alliance (Golden Deer): A merchant-dominated republic with internal squabbling, commerce-driven diplomacy, and a casual indifference to tradition.

The gameplay difference is subtle, but the symbolic structure is firm: each house’s combat roster, narrative arc, and post-timeskip political reality reflects their governing philosophy. Edelgard’s Adrestia is ruthless and efficient—limited healers, strong offense. Dimitri’s Faerghus fields knights and lancers bound by chivalry. Claude’s Leicester thrives on range and unorthodoxy—archers, tricksters, wild cards.

Fire Emblem makes faction design political pedagogy. You don’t just pick a team—you inherit its worldview. And the war that follows is as much about ethical divergence as it is about map control.

II. XCOM: Bureaucracy and Global Anxiety

XCOM, particularly Enemy Unknown and XCOM 2, presents a more modern, dystopian allegory. Here, you command a small paramilitary organization defending Earth from alien invasion—a premise seemingly devoid of political nuance. But peel back the surface, and XCOM becomes a study in cold war logic, neoliberal failure, and global crisis mismanagement.

Let’s begin with the XCOM Council—a shady coalition of world powers funding your operation. They:

- Issue vague directives,

- Penalize perceived failures (regardless of local context),

- And ultimately abandon you the moment their individual interests are threatened.

This isn’t just flavor text. It’s a simulation of international coordination collapse. As you prioritize missions, you’re constantly forced to triage geopolitically: Do you save Mexico or India? China or Germany? There’s no “right” answer—only losses you delay. The Council’s panic meter quantifies the fragility of global trust. As countries withdraw, funding vanishes, reflecting the conditional and transactional nature of modern alliances.

Then XCOM 2 flips the script: the Council failed, Earth fell, and XCOM becomes a guerrilla resistance operating within a surveillance state. You’re no longer coordinating states—you’re exploiting them. Your missions sabotage infrastructure, spread propaganda, and support localized uprisings. The game’s “factions” (Reapers, Skirmishers, Templars) each offer not just gameplay perks, but ideological positions on how to resist tyranny:

- Reapers: Espionage and secrecy.

- Skirmishers: Defectors from the enemy, seeking redemption.

- Templars: Zealots of psychic power, believing resistance is spiritual.

Your relationship with each group requires management—neglect one, and they withdraw. Support another too heavily, and equilibrium collapses. This mirrors real-world coalition management, insurgency dynamics, and the uncomfortable truth that “freedom fighters” rarely agree on what freedom means.

III. Tactics Ogre: Power in Paradox

Let Us Cling Together, the most celebrated entry in the Tactics Ogre franchise, may be the most overtly political TRPG ever made. Inspired by the Yugoslav Wars, it simulates ethnic conflict, military occupation, and nationalist ideology—and it pulls no punches.

The game’s central moral axis splits early: do you obey orders to massacre a village for political optics (Law route), or refuse and go rogue (Chaos route)? Each choice triggers diverging factional alignment:

- Bakram: Elitist authoritarians who support centralized rule and are backed by foreign powers.

- Galgastani: Ethnic majority nationalists engaging in genocidal purification.

- Walister: The oppressed ethnic minority fighting for autonomy (your people), who are not above moral compromise.

Unlike many games, there is no clean route. Every faction commits atrocities. Every victory is stained. Tactical choices are not just unit optimization, but political alignment.

Even units have ideology baked in: some soldiers will leave your party if your decisions violate their beliefs. The Loyalty system ensures that moral cohesion has mechanical weight. You may lose your best knight not to death, but to disillusionment.

In Tactics Ogre, the battlefield is a civil war—factional alignment is personal, historical, and unstable. The game isn’t asking “who is right?” It’s asking “who survives long enough to rewrite history?”

IV. Triangle Strategy: Governance as Combat

Square Enix’s Triangle Strategy (2022) is often seen as a spiritual successor to Tactics Ogre and FFT, and its core mechanic reflects a new evolution in political simulation: vote-driven tactical outcomes.

The game’s factions are less about ethnicity and more about resource control:

- Glenbrook: Aristocratic monarchy.

- Aesfrost: Militarized industrial state.

- Hyzante: Theocratic oligarchy with a salt monopoly.

These factions clash over trade, religion, and sovereignty—but the twist is that your party doesn’t simply follow your command. You must persuade them via the Scales of Conviction: a literal voting system that determines major story branches.

Mechanically, you:

- Gather information,

- Debate with party members,

- Influence the vote through argument and prior actions.

Thus, faction choice becomes an exercise in diplomacy, not just preference. You’re not a king; you’re a coalition-builder.

And again, the game does not reward idealism. Every faction has its sins. Glenbrook tolerates corruption. Aesfrost embraces meritocratic cruelty. Hyzante enforces religious tyranny through salt rationing. Allegiance is always compromise, and your ability to lead lies in how well you can frame that compromise to your allies.

V. Allegory in Mechanics: How Design Embeds Ideology

So what do all these games teach us?

They show that factions are more than lore. They are:

- Gameplay rule sets that simulate ideology.

- Resource constraints that model political priorities.

- Moral choices that reflect the cost of loyalty.

Consider:

- A faction that fields mostly heavy units with limited healing is probably simulating brute-force authoritarianism.

- A rebel group with limited funds but access to terrain advantages suggests asymmetrical warfare—possibly anti-colonial.

- A bureaucracy that penalizes failure while underfunding success reflects the logic of modern managerial states.

In this way, mechanical expression becomes political commentary.

VI. Conclusion: Allegiances as Analysis

When we choose a faction in a tactical RPG, we are not just picking a color or banner. We are selecting a governing style, a worldview, and—if the game is doing its job—a moral lens.

Fire Emblem makes us educators in ideological warfare.

XCOM turns us into agents of collapsing empires.

Tactics Ogre drowns us in blood-stained nationalism.

Triangle Strategy forces us to debate, vote, and compromise.

Each system, each map, each deployment is a small civics lesson—delivered in turn order.

And perhaps, in a world where political theory is either gamified or ignored, these games offer something rare: a simulation where ideology has consequences, and leadership is not won, but constantly re-evaluated.

So next time you align with a faction, ask not just “what are their units like?” Ask:

- Who writes their laws?

- Who dies for their cause?

- And who gets to choose what victory means?