Exploring the Narrative Significance of Losing and Restarting

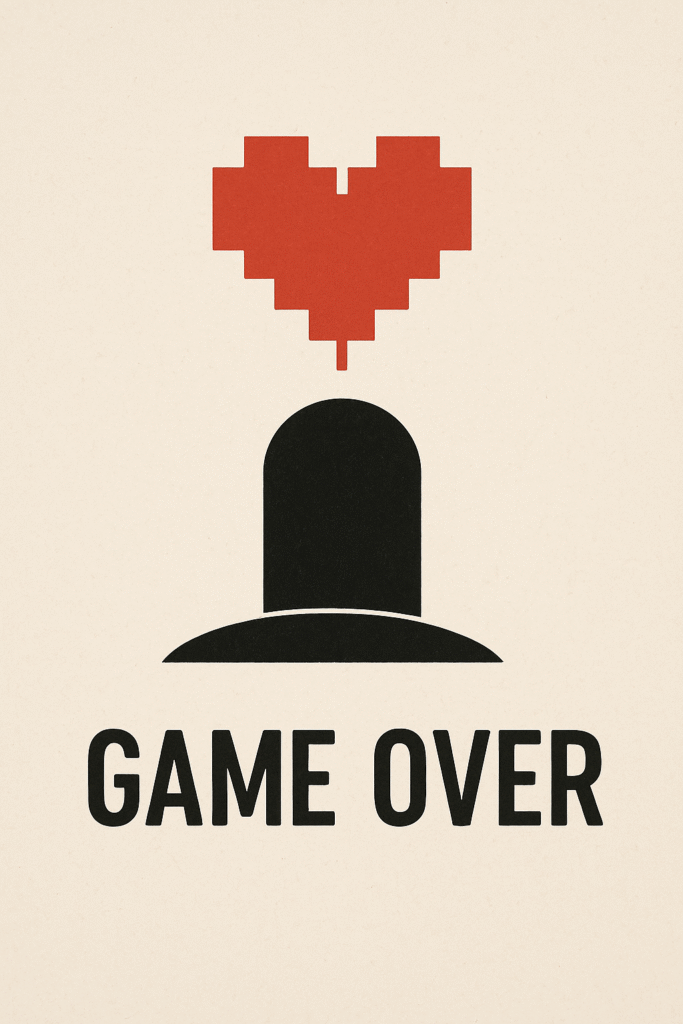

In most games, “Game Over” is treated as a punishment. A dead end. A screen that tells you: try again, but do better. It’s an interruption in progress, a consequence of mistakes, or just the result of bad luck. But what if failure isn’t just a setback? What if it’s part of the story—a mechanic with meaning?

In recent years, more designers have embraced failure as a deliberate narrative device, not just a mechanical necessity. Losing becomes more than a state—it becomes a theme, a lesson, a message. In this article, we explore how games use “Game Over” screens, restarts, permadeath, and loops to deepen immersion, explore character, and make failure feel not like rejection—but revelation.

I. The Traditional Role of Game Over

Historically, “Game Over” originated in arcade culture. It served one purpose: to make you pay again. You lost your lives, your credits, your chance—and you’d need to feed the machine for another go.

As games moved to home consoles, this structure remained. Three lives. Continue screens. Password systems. Failure was a roadblock, and often a deeply frustrating one.

The implicit message? You failed the game. Try harder.

But as narrative depth increased, and as roguelikes, RPGs, and immersive sims expanded player expectations, “Game Over” became more than a failure screen. It became a storytelling opportunity.

II. Failure as Learning Loop

Many modern games treat failure as part of the design loop, not a reset button.

Hades

In Hades, dying isn’t just a setback—it’s the way forward. Each time Zagreus falls in battle, he returns to the House of Hades, where new dialogue, character development, and narrative revelations await. Failure fuels story progression.

The game reframes dying not as failure, but as exploration. Every run teaches you more about the systems—and the characters. Death becomes lore.

Returnal

In Returnal, dying is woven into the game’s identity. You play a pilot trapped in a time loop on a hostile alien planet. Each death restarts the cycle, but echoes remain—both narratively and mechanically. The sense of existential repetition is core to the experience. The more you fail, the more you understand what kind of nightmare you’re in.

Here, Game Over is not just expected—it’s inescapable. And that helplessness is the point.

III. Permadeath and Consequence

Some games use failure to permanently reshape the world. These are high-stakes experiences where mistakes can’t be undone—and where narrative weight comes from irreversibility.

Fire Emblem (Classic Mode)

In older Fire Emblem titles, units who fall in battle are gone forever. These aren’t just numbers—they’re named characters with support conversations, personal arcs, and roles in the story.

Choosing whether to restart a chapter to save a favorite, or to press on and accept their loss, creates emergent narrative. It makes death matter. It forces players to ask: what does it mean to lose someone and keep going?

XCOM Series

XCOM thrives on tension. When a veteran soldier dies because of a 90% miss, it’s heartbreaking. But you learn. You adapt. Your base still needs defending.

Permadeath in XCOM creates stories of sacrifice, desperation, and resilience. It’s not just about squad wipes—it’s about how you recover.

IV. The Loop as Narrative Metaphor

Roguelikes and roguelites often integrate death into their structure. But many also use loops as narrative metaphors.

Outer Wilds

In Outer Wilds, the universe resets every 22 minutes. You’re an explorer uncovering the secrets of a dying solar system. You retain knowledge between loops, but not physical progress.

Failure here isn’t just dying—it’s missing something. Every Game Over teaches you something real. And when you finally piece together the truth, it feels earned—not through combat or puzzles, but through repetition and reflection.

The loop isn’t just a gimmick. It’s the thematic core—an exploration of time, legacy, and entropy.

V. Game Over as Narrative Punctuation

Sometimes, failure is rare—but when it happens, it matters deeply.

Spec Ops: The Line

This third-person shooter lures players in with familiar genre tropes, only to unravel into a psychological horror narrative. Failures—mechanical or moral—are not always preventable. When players are forced into actions they later regret, failure becomes a statement, not a punishment.

The narrative asks: Are you the hero you think you are? And the answer is often delivered not in cutscenes, but in player-driven consequences. Game Over isn’t always a death—it’s a reckoning.

VI. Games That Acknowledge Your Failure

Some titles break the fourth wall to comment on the act of failure itself.

Undertale

In Undertale, your choices—and restarts—are remembered. The game knows when you reload a save to get a different outcome. It doesn’t forgive. It doesn’t forget.

This makes Game Over feel emotionally charged. Choosing to kill or spare enemies changes not just your path, but the world’s memory of you. Your failures aren’t just setbacks—they’re permanent moral data.

NieR: Automata

In NieR: Automata, dying doesn’t just restart your run. It becomes part of the game’s philosophy. Your consciousness is uploaded. Your memories are fragmented. Each restart feels mechanically justified—and narratively significant.

The game’s multiple endings often rely on failure—not just in battle, but in choices. Ending W? Walk away from the final boss. Ending K? Eat a mackerel that kills you instantly. These aren’t jokes—they’re meta-commentary on control and consequence.

VII. Failure That Reshapes the Game World

Some games allow failure to permanently alter the status quo, turning death into world state rather than a reset.

Pathologic 2

This surreal survival narrative challenges the player to maintain health, hunger, fatigue, and sanity—simultaneously. Failure is constant, and restarting is discouraged. Every death leaves a scar on the world. Your choices degrade your standing, worsen the town’s condition, and reshape future encounters.

The game dares you to fail forward—to live with your mistakes. Game Over is never the end. It’s a continuation, with consequences that haunt you.

VIII. When Losing Tells a Better Story

Not all games need death to tell a story. But many of the best narratives emerge when the player doesn’t succeed. Failure creates:

- Vulnerability: You’re not invincible.

- Reflection: You examine your choices.

- Adaptation: You change your approach.

- Growth: You feel your own progression.

Winning teaches you what works. Losing teaches you why things matter.

IX. Designing Failure with Intention

For failure to be meaningful, it must be designed deliberately. Sloppy checkpointing, arbitrary difficulty spikes, or opaque fail states do not create compelling narratives—they create frustration.

Meaningful failure involves:

- Consequences that persist

- Narrative justification

- Emotional or thematic feedback

- Player learning and agency

In the best designs, failure is inevitable, intentional, and illuminating.

Conclusion: Game Over Isn’t the End

The words “Game Over” used to mean defeat. Now, they can mean transition. A new cycle. A chance to understand the world, the system, or the self in a deeper way.

Failure, when embraced as a mechanic and message, offers designers and players something rare: honesty. It says, “You are not always in control. Not everything can be fixed. But you can still continue.”

In these moments, games stop being mere challenges—and become stories of persistence, transformation, and humanity.

So the next time you see that Game Over screen, don’t just reload.

Ask what it’s trying to tell you.