A Breakdown of Flow and Downtime in Isometric RPG Structure

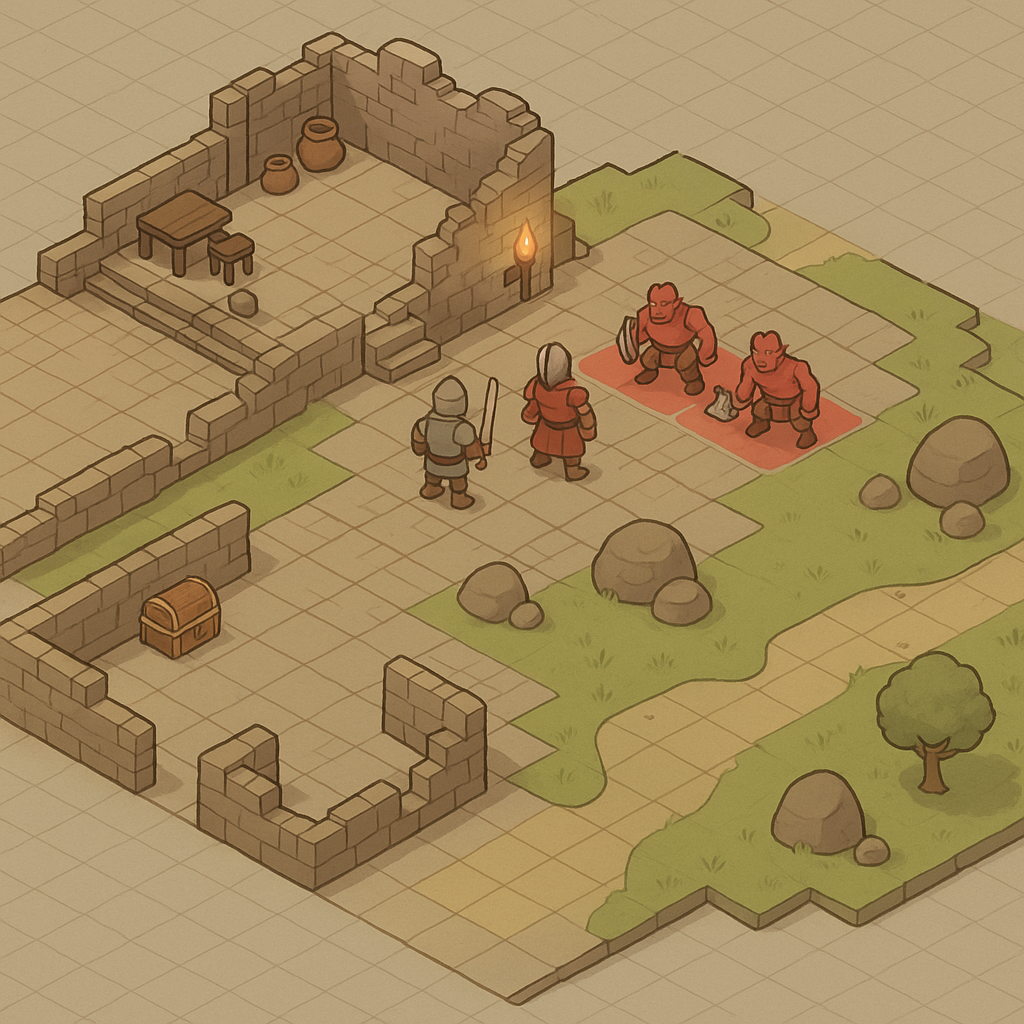

Isometric RPGs and tactical grid-based games are often praised for their deep combat, layered systems, and narrative flexibility. But what keeps players truly engaged isn’t just the battles—it’s the pacing between them. The most successful grid-based games balance their design across a spectrum of active space (combat) and idle time (preparation, traversal, interaction).

This blog explores how pacing works in isometric RPGs, focusing on how developers manage tension, rhythm, and player flow through spatial layout and gameplay cadence. Whether it’s in tactical battlegrounds like Divinity: Original Sin 2, turn-based epics like Baldur’s Gate 3, or genre hybrids like Fire Emblem, the use of time and space plays a critical role in how these games feel—and why we return to them.

I. Defining Active and Idle States in Grid-Based Play

In traditional design theory, “pacing” refers to how fast or slow a player experiences content. In grid-based RPGs, pacing isn’t just about story beats—it’s about engagement rhythm, often segmented into two distinct states:

- Active Space: The player is in a combat scenario. Every action matters. Tension is high. The grid becomes a chessboard, with movement and positioning central to success.

- Idle Time: The player is exploring, resting, managing inventory, customizing characters, or making dialogue choices. The grid may still exist, but pressure is low, and decisions aren’t immediately tactical.

Effective games alternate between these states, not randomly, but purposefully, creating a loop of investment, reflection, and re-engagement.

II. Combat as Spatial Compression

Combat in grid-based RPGs takes place on limited, highly curated space. Every tile has value:

- Terrain offers bonuses or penalties

- Enemy locations limit or encourage movement

- Spell areas and weapon ranges define zones of control

These spaces are tightly compressed in purpose. There is no wasted tile. Each battlemap is a stage, and the performance is a puzzle of player intent vs. enemy design.

Because each action in battle is deliberate, combat becomes mentally taxing. That’s not a flaw—it’s the genre’s appeal. But without downtime between fights, players would quickly experience fatigue.

The pacing challenge, then, is how to let the player breathe without breaking immersion.

III. The Role of Downtime

Idle time isn’t filler—it’s relief. It gives players space to:

- Review character builds and inventories

- Reflect on outcomes of previous battles

- Make narrative choices without pressure

- Interact with the world at their own pace

These moments transform raw mechanics into roleplay.

In games like Tactics Ogre or Disgaea, downtime occurs on the world map or in hubs where units can be upgraded and equipment managed. In more narrative-rich games like Baldur’s Gate 3, downtime is literally a campfire—a space where characters bond, rest, and deliver some of the most intimate moments in the story.

Downtime acts as a contrast agent: by slowing the rhythm, it makes combat feel sharper when it returns.

IV. The Importance of Spatial Rhythm

Even outside of combat, space communicates pacing.

Tight, Cluttered Spaces

- Create tension

- Encourage fast transitions to combat

- Restrict options (corridors, alleys, chokepoints)

Open, Expansive Zones

- Encourage exploration

- Invite narrative engagement

- Signal breathing room between fights

For example, Final Fantasy Tactics uses narrow, detailed battlefields, but its overworld is a simple map with nodes. This clear delineation keeps pacing smooth. Players know when they’re in a battle and when they’re choosing their next step.

Meanwhile, Divinity: Original Sin 2 blurs the line: its sprawling isometric maps are used for both combat and exploration. Battles may erupt at any time. To maintain pacing, the game varies density of encounters—light exploration areas alternate with heavier combat zones.

V. Narrative Flow and Turn-Based Cadence

Grid-based RPGs are inherently turn-based, which means pacing is already controlled. Unlike real-time games, nothing happens unless the player chooses it to happen. This empowers players to set their own pace—but it also introduces risk of stalling.

To combat this, good games:

- Vary battle objectives (not just “defeat all enemies”)

- Introduce timers or reinforcement triggers to increase urgency

- Tie narrative to mechanics (e.g., escaping a burning fortress or protecting a civilian)

In Fire Emblem: Three Houses, pacing is further regulated by the calendar system. Each week, players decide how to spend time—train, explore, or rest—before returning to the battlefield. This injects a looped rhythm that players learn to anticipate and optimize.

Narrative-heavy pacing keeps tension alive even when the swords are sheathed.

VI. Encounter Frequency and Player Agency

Not every game uses combat as its core pacing device. Some, like Pathfinder: Kingmaker, feature stretches of exploration or dialogue with few fights. Others, like XCOM, deliver mission after mission in rapid succession.

The best grid-based RPGs give players control over how much combat they face. This can be accomplished through:

- Optional encounters (random or visible)

- Scalable difficulty

- Sandbox-style mission selection

- Travel systems with risk/reward trade-offs

By giving players agency over pacing, designers let them adjust the balance of idle/active time to suit their preferences.

VII. Environmental and Audio Cues

One overlooked aspect of pacing is tone signaling. Players need to intuitively feel when they’re safe and when danger looms.

Smart design uses:

- Ambient music to signal exploration

- Tense percussion for nearby combat

- Lighting and particle effects to indicate hostile zones

- Enemy placement to warn or surprise

In Shadowrun: Dragonfall, environmental layout and dialogue pace hint when combat is likely. The game rarely surprises players unfairly—it lets you feel the flow building.

This helps the player mentally shift gears. The space becomes emotionally charged, even before the battle begins.

VIII. The Trap of Monotony

Bad pacing in grid-based design typically stems from:

- Too many filler encounters

- Repetitive combat objectives

- Lack of non-combat engagement

- Overly linear maps with no discovery value

When every encounter feels the same, and every space serves the same function, players begin to check out.

Strong games counteract this by:

- Offering alternate paths and hidden objectives

- Varying combat geometry and terrain use

- Introducing new enemy behaviors or faction politics

- Incorporating social systems or narrative dilemmas mid-mission

Pacing isn’t just fast or slow—it’s varied.

IX. Designing Pacing Loops

Effective pacing in grid-based RPGs follows a loop:

- Setup Phase – Exploration, conversation, decision-making

- Tactical Phase – Combat or puzzle resolution

- Relief Phase – Reflection, reward, story advancement

- Preparation Phase – Upgrades, training, repositioning

Each part builds anticipation for the next. When this loop is disrupted—either through unbalanced difficulty or poorly spaced encounters—the game loses its rhythm.

Great games trust the player to rest and challenge them to re-engage.

Conclusion: Breathing Between Battles

Grid-based RPGs aren’t just about tactics. They’re about tempo—the quiet before the strike, the planning before the clash, the recovery after the storm.

By alternating between idle time and active space, isometric RPGs create a sense of flow that’s as compelling as any plot twist or boss fight. It’s in the rhythm of decision-making, the silence between skirmishes, and the shape of the map itself.

To pace a grid-based game well is to compose a song of pauses and peaks—letting each beat resonate before the next one hits.

So next time you camp between missions, wander through a town square, or rearrange your party in silence, remember: that’s not wasted time.

That’s part of the story.